Emerson reaches his wish goal

Emerson's wish to meet the Kookaburras Australian hockey team has come true, with the Brisbane boy joining the team for five fantastic days.

Soreness

Diagnosis takes time

Emerson hits the hockey ball with real intent. So much so that, when his shoulder got sore after the hockey season finished in 2018, doctors thought it was just from walloping the ball at the net.

In December 2018, Emerson also hurt his shoulder on a water slide. But, again, doctors said any pain must be related to that sunny day on the slide.

But in 2019, when Emerson couldn’t lift his arm and wasn’t sleeping at night, mum Jacinta began to worry.

She took her then-7 year old for an ultrasound.

“That’s when we rushed to the hospital,” Jacinta said.

“I do remember the oncologist saying to me ‘Emerson is a very sick boy’.”

It took some months, but doctors finally diagnosed Emerson with Stage 4 Ewing Sarcoma, a bone cancer.

His primary tumour was in his spine and another in his neck. His left arm became paralysed.

Treatment

Ups and downs of medical journey

Jacinta remembers an oncologist telling her “not to Google” Ewing Sarcoma. Doctors told her Emerson had a long road in front of him.

“They did say it was going to be a very intensive 12 months of treatment, which it was,” Jacinta said.

“They gave him chemo every fortnight whereas most cancers it’s every month – they had to hit him hard.”

Emerson responded well to his treatment, not experiencing bad nausea and often returning home after chemotherapy to play basketball in his backyard. The hiccups came in the second half of his year of treatment when he began having radiation and chemotherapy at the same time.

“The radiation was burning the inside of his throat, so he ended up with chronic throat pain,” Jacinta said.

“At one stage, we went into the hospital, and he was vomiting up blood.”

Emerson’s throat was so red raw that it was bleeding.

“Emerson was on intravenous morphine for pain; he wasn’t eating or drinking,” Jacinta said.

“That was so hard to watch. There is nothing you can do; it’s horrible.

“Then he had to have a nasal gastric tube because he couldn’t swallow – the pain involved in putting that tube in, watching my child get that was probably the lowest point.”

Normality

Milestones for Emerson

Emerson had been itching to play hockey while he was going through his cancer treatment. He pleaded with his doctors, but they said he couldn’t play.

So when his treatment finally ended in May 2020, Emerson couldn’t wait to pick up his hockey stick.

His first game back was in June, a month after he became cancer-free.

“It was so nice to see him doing normal things, doing things other 8 year olds do. Not having to worry anymore,” Jacinta said.

It is customary for hospital staff to send off children who beat cancer with a bell-ringing ceremony. But with COVID sweeping Australia in 2020, Emerson’s exit from the hospital was low-key.

Instead, Jacinta bought her own bell, and a few months later, in September, she gave Emerson a special 9th birthday party.

“I did the bell ringing at home with about 20 people, everybody who went through the journey with us,” Jacinta said.

Jacinta presented Emerson with a trophy.

“It had his name on it,” Jacinta said. “And it said ‘for courage and bravery, 2019-2020’.”

Wish trip

Hanging with Kookaburras

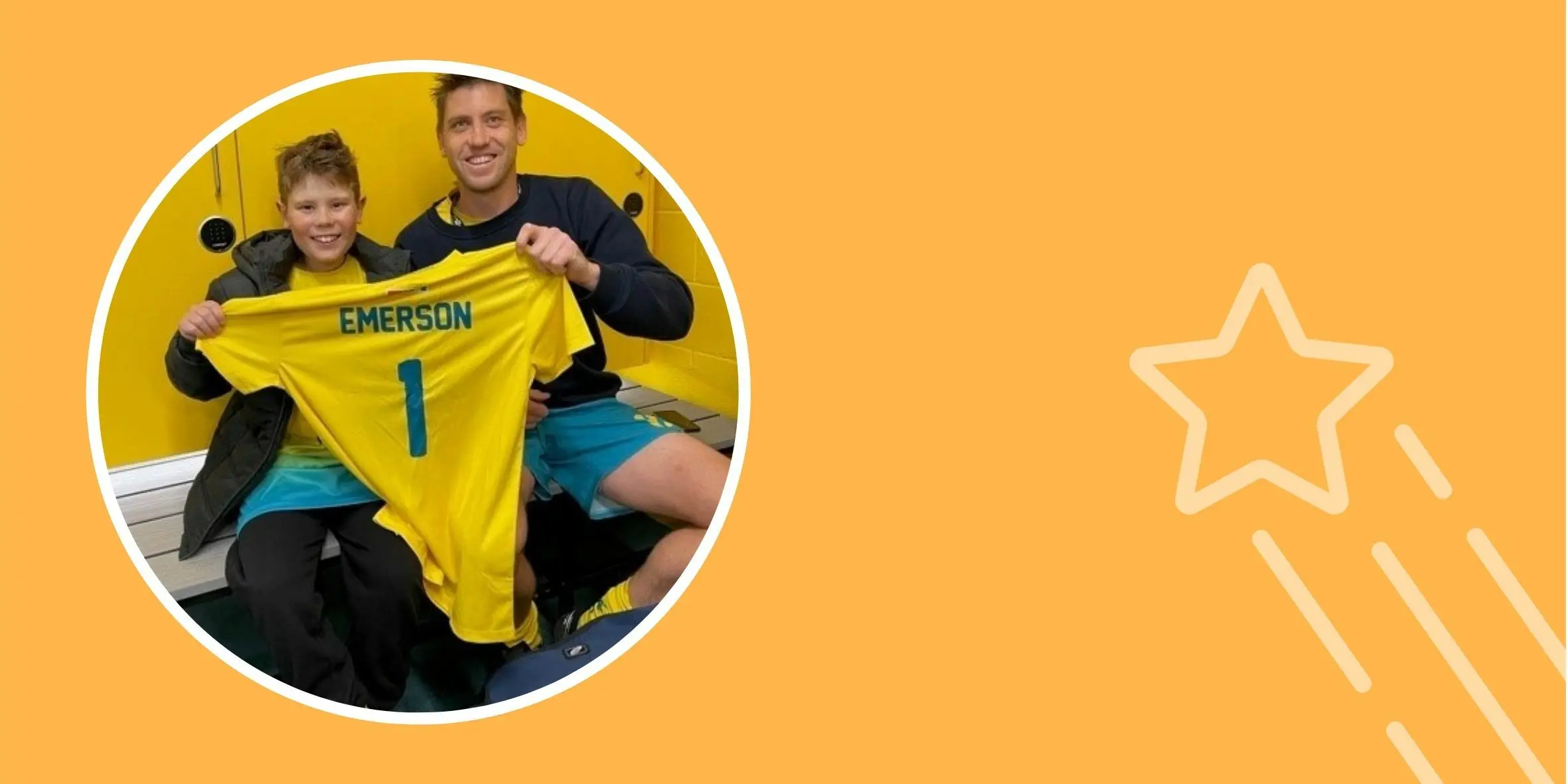

Emerson’s wish was to meet the Australian men's hockey team, the Kookaburras.

He had started playing hockey when he was four and, according to Jacinta, “lives and breathes hockey”.

“I told Emerson to think of something I could never do for him,” Jacinta said. “So he always said he wants to captain the Kookaburras one day, and we thought that sounded like an awesome wish.”

Emerson travelled from his home in Brisbane to Perth to meet the Kookaburras and watch them play against New Zealand.

Jacinta said she and Emerson spent five days in Perth and came into contact with the Kookaburras every day.

“It blew our expectations out of the water,” Jacinta said.

“The Kookaburras treated him like their little brother. He was included in training, their lap of honour after the game, and then took him into the rooms to do the warm downs and the team song. They couldn’t have done any more for him.

“They even included him in the group team photo. Then the women’s team, the Hockeyroos, included him and took him on the field to train with them. And both teams gave him a huge bag full of merchandise.”

Emerson said the Kookaburras went out of their way to make him feel welcome.

“When we were coming out of the hotel, and we saw them, they said ‘how did you sleep’ and ‘are you excited for the game’,” Emerson said.

Wish effect

Positive memories replace sad ones

Jacinta said Emerson’s wish had only strengthened his resolve to become a professional hockey player when he grows up.

“Who knows, in 10 years, he might be running on the field as a real player. It would be really nice if something like that happens,” Jacinta said.

In the meantime, Jacinta said she and Emerson would cherish their memories of their wish trip.

“We often say ‘remember when you were in hospital doing that’ or ‘how much you hated the needles’, but since the wish trip, it’s changed to ‘oh remember when the players did this’ or remember when we were in the hotel, and this happened’. So it’s changed our memories,” Jacinta said.

“We have replaced those sad memories with fantastic ones.

“This is something that will be in Emerson’s memory for the rest of his life. I can’t speak highly enough of Make-A-Wish Australia. Everyone will get sick of hearing about the wish because I’ll be talking about it for months!”

We have replaced those sad memories with fantastic ones

Jacinta, mother of Emerson Ewing Sarcoma

The Wish Journey

How a wish comes to life

Make-A-Wish volunteers visit each child to capture their greatest wish, getting to the heart of what kids truly want and why. This profound insight is part of what makes Make-A-Wish unique, giving children full creative control and helping to shape their entire Wish Journey.

Back at Make-A-Wish HQ, we partner with families, volunteers and medical teams to design the ultimate wish experience - and start rallying our partners and supporters to help make it happen.

In the lead up to the wish, we take each child on a journey designed to build excitement and provide a welcome distraction from medical treatment. Anticipation can be incredibly powerful, helping to calm, distract and inspire sick kids at a time they need it most.

When the moment finally arrives, children get to experience their greatest wish come true - it's everything they've imagined and more. Pinch yourself, and don't forget to take a breath and enjoy every precious moment!

Wish impact studies show that a child's wish lives on, long after the moment. A wish gives more than just hope – with an incredible and lasting effect on the lives of sick kids, their families and wider communities.